Dispelling Three Common Myths About Electric Vehicles

The future for automobiles is electric.

According to a new survey from the automotive club AAA, the “American appetite for electric vehicles is heating up”. The 2018 survey found that one-in-five Americans are likely to go electric for their next car purchase – up from 15 percent in 2017.

Automotive manufacturers have anticipated this growing consumer interest in electric vehicles (EVs). Many U.S. companies, including Ford and General Motors, have outlined aggressive plans to shift from gas-combustible to electric cars. Ford, for example, recently announced investments of $11 billion in electric vehicle research and production by 2022. The company plans to have 16 fully electric vehicles in its lineup by that time – with an addition 26 plug-in, hybrid vehicles.

Global automotive manufacturers are getting in on the action too – perhaps even more so than U.S. companies. Last fall, Volvo announced that starting in 2019 every single Volvo vehicle will run, at least in part, on electric power. The Swedish manufacturer intends to roll out five fully electric vehicles between 2019 and 2021, “along with a cavalcade of plug-in hybrids and 'mild hybrids', which supplement internal combustion engines with batteries and motors”.

Yet, despite the recent surge in consumer interest (and the ensuing manufacturing transition), there is still a lot of misinformation being propagated about electric vehicles – much of it outdated, long-debunked relics from the early days of electric vehicles when prototype technologies were expensive, inefficient and frankly not ready for widespread consumer adoption.

However, those days are long gone. The landscape of electric vehicles is completely different today than even just five or 10 years ago, yet misinformation lingers. Let's take a look at three such myths and some of the fact-based reasons why these are best left in the past.

Myth 1: The range for electric vehicles is too limited

Historically, range anxiety has been one of the major reasons why American consumers have been wary of purchasing an electric vehicle. And for good reason. Once upon a time, many electric vehicles had battery ranges of well under 100 miles, and charging stations were few and far between.

However, according to a recent report by the Department of Energy, “the median all-electric vehicle range [grew] from 73 miles (117 km) in model year 2011 to 114 miles (183 km) in model year 2017 of EVs” in the U.S. Yet, while the growth of the median is encouraging, the best-performing EV models now have ranges two or three times this much. The mass-market Tesla Model 3, for example, has a 220-mile range, and the luxury Tesla Model S has an option for a 335-mile range. Apart from Tesla, the 2017 Chevy Bolt EV features an impressive 238-mile range, while being priced at under $40,000.

However, according to a recent report by the Department of Energy, “the median all-electric vehicle range [grew] from 73 miles (117 km) in model year 2011 to 114 miles (183 km) in model year 2017 of EVs” in the U.S. Yet, while the growth of the median is encouraging, the best-performing EV models now have ranges two or three times this much. The mass-market Tesla Model 3, for example, has a 220-mile range, and the luxury Tesla Model S has an option for a 335-mile range. Apart from Tesla, the 2017 Chevy Bolt EV features an impressive 238-mile range, while being priced at under $40,000.

Innovation in battery technology is not the only solution to range anxiety, though. EV-charging technology has improved alongside battery technology in recent years, notably reducing the required charge time, and EV charging stations are much more widely available now than just a few years ago.

Tesla’s well-publicized Supercharger network, for example, now has over 1,200 charging stations located across the U.S., with thousands of additional stations on the way. This is an improvement over just eight Supercharger stations in existence back in 2013. Including Tesla’s proprietary chargers, there are now approximately 23,000 public chargers in the U.S., with thousands of more on the way as car manufacturers, EV-charging companies, municipalities and electric utilities all contribute to the growth.

Myth 2: Electric vehicles are more expensive to own

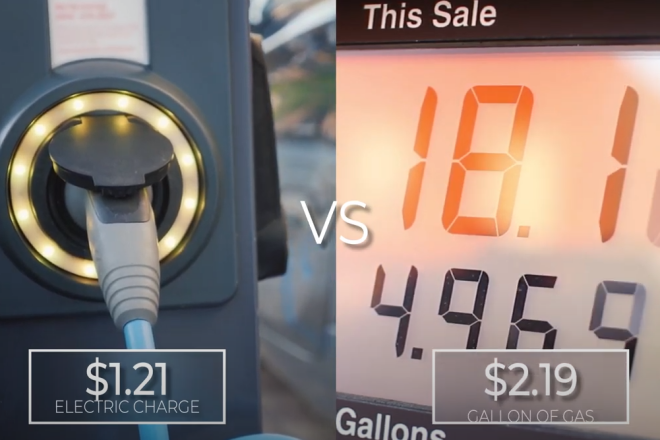

Here's another remnant from the early days of EVs that perpetuates despite evidence to the contrary. Yes, the retail price for a new electric vehicle is typically somewhat higher than a comparable conventional vehicle (For example, a 2018 Nissan LEAF retails at $30,000 compared to a $19,000 Toyota Camry). However, according to a recent analysis from the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute, “running an EV is almost always cheaper – sometimes dramatically so”.

The study based its figures on the average costs of electricity and gasoline in all 50 U.S. states at the end of 2017 and assumed an annual driving distance of roughly 11,500 miles, which was the national average for 2015. Using this methodology, the researchers showed that EVs could save drivers about $1,000 each year in fuel costs. For example, drivers in the State of Washington would spend about $1,338 on gasoline or just $372 on electricity for an entire year. In Hawaii, where both electricity and gasoline are much higher than the nation's average, drivers would still save about $400 each year with an electric vehicle.

Yet, lower fuel costs are not the only factor in play here. According to another study from the University of Leeds, the total cost of ownership (TCO) was lower for EVs in all of the four regions tested: Japan, the United Kingdom, California and Texas. In addition to fuel costs, the researchers note that both government subsidies/incentives and lower lifetime maintenance costs of EVs contribute to the lower TCO.

Myth 3: Our power grid can't sustain electric vehicle charging

Myth or fact? Unlike the other two myths, this is slightly more nuanced. While some have grossly exaggerated that EV charging will cause the power grid to “crash”, there is some truth in this hyperbole.

According to a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Colorado, current grid infrastructure can handle nearly eight million additional plug-in electric vehicles (Note that the U.S. is yet to reach one million in EV total sales). Beyond this figure, there certainly could be issues with the power grid, especially if EV owners in a clustered area are all charging during the evening when power usage spikes.

According to a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Colorado, current grid infrastructure can handle nearly eight million additional plug-in electric vehicles (Note that the U.S. is yet to reach one million in EV total sales). Beyond this figure, there certainly could be issues with the power grid, especially if EV owners in a clustered area are all charging during the evening when power usage spikes.

However, the NREL report points to the necessity of investments in grid modernization and smart grid technology that can optimally balance the power grid and enable programs that encourage EV charging at ideal times. Investments in public EV charging stations can also help manage the electricity demand from electric vehicles.

Many utilities, especially those in areas with a lot of electric vehicles, like California’s Big Three (Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric), are already well on their way to modernizing power grid infrastructure for the oncoming growth of EVs. Others have a long way to go. But many of the investments required to prepare for electric vehicles offer other benefits to our society, including fewer power outages and more efficient energy usage.

So, do you think you’ll be in that 20 percent of Americans who will purchase an EV for their next car? Whether you are or not, the electric future is on the way, and you’re likely to see many changes in your area to accommodate the growth of EVs.

Interested in learning more about electric vehicles? Keep an eye out for our electric vehicles fact sheet publishing later this summer, which will provide you with more information about owning and operating an electric vehicle today.